A few months ago I received an email from Rob André Stevens with some material for the site related to Elias Howe, Jr. An excerpt of the email follows:

“I also find it odd that your site doesn’t even show a picture of him on your ‘Rank and File’ page, as it would seem as a semi-historian of the Regiment, you’d be aware of this man’s accomplishments, as he was also instrumental in the original forming of the 17th, and used much of his wealth in its benefit at various times during his enlistment…”

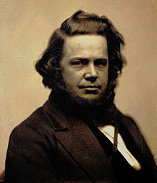

To be sure, there hasn’t been an image of Howe on the site until today. Here is a little more about Howe and the 17th CVI:

The accomplishments of Elias Howe, Jr. are fairly well known to many folks and especially to those people who have lived in the Bridgeport, CT area for any length of time. Howe is generally recognized as the inventor of the modern sewing machine, certainly the first to patent a design for a truly workable machine. These patents made Howe a wealthy man in the years before the Civil War, although not without years of expensive legal battles to defend his patent.

From childhood Howe was afflicted with some sort of physical disability (described as a sort of “lameness” by most biographers of the period). Nevertheless, at the onset on the Civil War there was little question as to where his loyalties lay.

Howe, born in Spencer, MA, maintained an interest in the regiments formed in that area as well. In 1861, at Fort Massachusetts outside of Arlington, Virginia, Howe presented the Colonel and Lieutenant Colonel of the 5th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry (3 months) a fully equipped stallion. The news reports of the time indicated that Howe did this for the regiments entire Field and Staff – not quite but generous nonetheless.

In August 1861 Howe was appointed president of a Union meeting called in response to a peace meeting that was held (and subsequently broken up rather violently) in Stepney (now a section of Monroe). This meeting, and its violent aftermath (including the sacking and burning of a “Copperhead” newspaper in Bridgeport), was reported on nationally. Howe reportedly said, in response to threats of gunfire by the peace protesters, allegedly told the attendees of the Union rally that if any gunshots were fired to burn down the whole town and that he (Howe) would pay for the damages.

Howe’s involvement with the 17th CVI began in earnest in the summer of 1862. That summer, following the call for 300,000 volunteers, saw Howe become on the first men in Bridgeport to volunteer in response. He is carried on the muster roll for Company D – to be known as the “Howe Rifles” – as Elias Howe, Jr., machinist. There is a statue of Howe in Seaside Park in Bridgeport located on the site where Howe was said to have slept on a bed of straw with the other recruits of the 17th CVI

Howe was far too infirm to see active service with the 17th CVI but still had a desire to assist the regiment in any way. As he did with the 5th Massachusetts the year before, Howe purchased and presented fully equipped horses to Colonel Noble and Lieutenant Colonel Walter. Howe clearly followed the regiment when it left Bridgeport, acting as postmaster for the regiment. He is mentioned in many soldier letters from that time period. For instance, from Sergeant James Bosworth of Company D (who also noted the difference between Private Howe and the average private in the regiment):

“Mr. Howe is unwell in Baltimore his son acting postmaster in his absence. He has brought him a wall tent like those used by our own officers and fitted it up in good shape and boards at the regimental officers dining tent at 3 1/2 dollars per week so that you can see how much he lives and fairs like a common soldier. He has got a horse and carriage from home, in fact he plays the gentleman as much as the highest ranked officer and id looked upon with as much respect. So much does the millionaire act the common soldier in the ranks of the Federal Army. But as this is no more than can be reasonably expected of one in his position all seem to be satisfied although by having such a man on our roll makes a little more duty for those who have to perform it. “

In some respects, Howe was no different than any other soldier of the regiment. Sergeant Augustus Bronson of Company C wrote back home that Howe was subject to curfew as much as the next soldier:

“E. Howe jr. got in the other night for in consequence of being out after 9 P.M. without the countersign, he carries the mail for the regt. and has a pass from the Col. to go and come when he pleases but the pass is not good from 9 P.M. untill the next A. M. so as he did not keep good hours that night he was cribbed.”

Perhaps the most notable example of Howe’s involvement with the 17th occurred in the winter of 1862. The last time the regiment had seen any pay occurred while they were still in Baltimore. As Colonel Noble wrote in his history of the regiment, “on one occasion, by permission of the Secretary of War, (Howe) advanced the pay of the regiment, about fourteen thousand dollars, on the march towards Fredericksburg.”

This act was noted by others as well – in a December 7, 1862 letter home Lt. Aldace Walker of the 11th Vermont wrote that his cousin, working in the Paymaster’s Office, was paid a visit some days earlier by a private in the 17th CVI asking to “buy the [muster] roll of the regiment.” Not sure what the private intent was, nothing came of it so the private went to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, where arrangements were made for the private, Elias Howe, Jr., to loan the government the money needed to pay the regiment.

However the event went down, the regiment was paid off on December 10th, as was noted by William Warren in his journal.

Howe remained on the rolls of the regiment as a private, even though he never fought in a single battle, until the regiment was discharged from the service in July 1865. His final act of generosity for his fellow soldiers during their time in the service was to charter a special train to bring the veterans back to Bridgeport from New Haven in early August, where they were greeted as returning heroes. As for Howe – he would not attend any of the annual reunions of the regiment he gave so much to. Howe, beset with illness, died at age 48 in 1867. In his honor, Bridgeport veterans named the Grand Army of the Republic, Post No. 3, the Elias Howe, Jr. Post.

2 comments for “Elias Howe, Jr. and the 17th”