Today marks the 150th anniversary of the 17th CVI’s introduction to combat in the Civil War. At around 5PM, after settling down to cook their evening meals, the full fury of Stonewall Jackson’s attack on the right flank of the Union Army’s XI Corps (well, the right flank of the whole Union Army) was felt. Postwar accounts, indeed, accounts written home shortly after the battle, tell the story of a regiment that believed an attack was imminent and that it was not going to be coming from the direction that they were told to expect it from. Well…maybe so and maybe not.

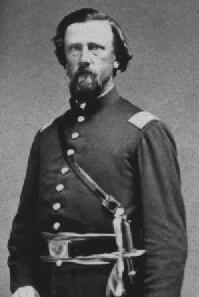

Lt. Colonel Charles Walter

What is certain is that this battle was not what the soldiers of the 17th CVI expected. Looking back over 150 years, it was not the sort of battle that they deserved (inasmuch as any sort of battle would be deserved). For certain, above the regimental level, it was not the type of leadership they deserved – that much anyone could (and should, from my perspective) agree on.

At this battle Colonel William Noble earned the lasting respect of his men and officers and was severely wounded in the process. This just a couple months after he had arrested nearly all his officers for putting their accusations of his incompetence in writing to their brigade commander.

Lt. Colonel Charles Walter, in his second battle (he was at First Bull Run and held prisoner for over a year), performed in the cool and detached manner the regiment had become accustomed to. After ordering the wing under his command to shelter and fire from behind a fence, he realized the hopelessness of their position. As he started to give the order to fall back he was shot through the eye and killed. Walter was the first of 3 lieutenant-colonels to die in combat in the 17th. It was not a good rank to hold in the regiment.

Company officers either acquitted themselves very well (which was most of them, it seems) or not so much so. Company D’s Captain William Lacey would resign shortly after the battle with whispers, insinuations and sometimes outright statements of cowardice under fire. The same held true for the non-commissioned officers and private soldiers. Some freely admitted that, in the face of certain death, they ran. Fast. And far. Many more stood and fought, and were captured for their trouble. Others gave ground stubbornly. All agreed it was a confusing, swirling blur of noise, smoke, and blood. In short, it was nothing like the stories that they had heard.

Somehow, in the midst of the retreat, many soldiers found the regimental colors and rallied behind the ever-popular Captain Douglass Fowler of Company A (waving his sword over his head and crying “Rally around the flag, Seventeenth!) and the irrepressible Corporal C. Fred Betts, holding the colors in one hand and a pistol in the other. Both would be promoted after this battle.

When I was a teenager, slightly interested in the Civil War, I came across the gravestone of my GGG Grandfather with the inscription “Co. E, 17th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry.” With visions of Civil War heroics in my head, I read the history of the 17th CVI and the XI Corps. Back then, most of that history read something like this – the XI Corps broke and ran, losing the battle for the Union. To my young, uneducated mind it was a disappointment compared to stories about the 20th Maine and others.

As is always the case, there is always more to any story than meets the eye. The story of the 17th at Chancellorsville is no different. There were heroes that day in and around the Talley Farm and there were those who faltered. Most simply did their job the best that they knew how. Some died doing that job, like Charles Walter – leaving a widow and young daughter behind. Some lived to write their own version of what happened, like William Warren (whose account in on this site). Many, many more merely survived.

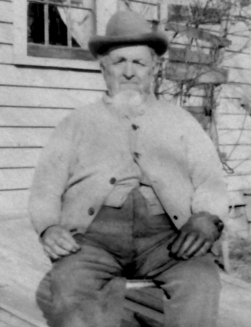

Private Benjamin Brotherton – Company E

My GGG Grandfather, Benjamin Brotherton (pictured to the left in his old age), was one of those men. Shot in the head, he spent the next few months in the hospital – missing Gettysburg as a result. But he survived the war, married, had a bunch of kids who had a bunch more kids, and so on until one day there was a teenager looking over his grave who was foolish enough to be disappointed that his service was not with a more “glamorous” regiment.

Private John Lewis, of Company D, wrote his wife after the battle:

“Oh, Augusta, if I could only sit down and relate to you the sights that I have seen of the field of battle. It is enough to break the stoutest heart to hear the cries and groans of the wounded and dying. There was a young man named Wm. Clark in our company that was wounded. As we were retreating, he was shot in the groin. The blood was flowing from him, covering the ground. He saw me as I was passing him and he called on me to help him. He said he was shot and could go no further. I took him and laid him over a little green mound, said goodbye and left him. I could not stay with him and would have been shot or taken prisoner. I had to leave, but I guess the poor fellow is dead and out of all misery…”

I think about that when I pass through William Clark’s neighborhood or the graveyard where a marker stands in his memory. John Lewis would die the following year – not from combat but from disease. I think about how lucky it was for me that Benjamin Brotherton was not one of those men.

So, 150 years later, older and wiser, I remember what they did leading up to that fateful day at the Talley Farm and beyond – to Gettysburg, to South Carolina and to their “cushy” service in Florida (where they lost their 3rd lieutenant-colonel in battle). In this day and age, where a power outage for a few hours is a hardship, I remember what they did and marvel at it. And I say “thanks” for doing it.