…my initial reaction to this headline:

“Skull of Civil War soldier found at Gettysburg to be auctioned”

The short version of the story is that the skull was found near the “Benner’s Farm” in 1949 and it was expected to sell for $50,000 to $250,00o to a collector. Really? From Katie Lawhorn, the spokesperson for Gettysburg National Military Park – “very unfortunate.”

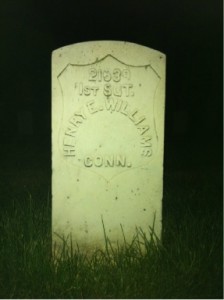

Benner Farm looking south/Dale Call photo

Assuming that the skull was found near the Josiah Benner farm – where 4 companies of the 17th CVI fought on July 1st and which served as a field hospital during the battle, and given the article’s description of the various Civil War artifacts found in close proximity to the skull, then it is not a stretch to imagine that the skull belonged to a soldier who fell during that portion of the battle. Not that this really mattered.

But – somewhere good taste, common sense and basic decency prevailed, because an hour ago the following story appeared in the online edition of the York (PA) Daily Record:

“Auction company says it will donate Gettysburg soldier’s remains”

Allegedly to the National Park Service. From the newer article:

“In the 20 years Lawhon has worked in Gettysburg, she’s never heard of soldier remains being for sale.

“In the past, there have been humans remains that have come into our possession,” she said.

The park doesn’t participate in archeological digs, as it believes all the battlegrounds are burial places for soldiers. The only exception would be if remains were disturbed, she said. In 1996, heavy rains along a railroad embankment disturbed human remains that were buried nearby, Lawhon said.

An expert from the Smithsonian Institute found lead splatter on the cranium of the young man, believed to have died in his 20s, she added.

He was buried on what they believe was the anniversary of his death based on what battles took place where he was found, Lawhon said.

“If we came into possession of the remains (in Hagerstown), we would do the same,” she said.

The sale of a Civil War soldier’s skull illustrates the need to preserve places such as Gettysburg, Lawhon said. The reason it was dedicated as a national park was to keep such things from happening.

“I think the right thing to do is get (the remains) to us,” she said, “and that’s what I hope happens.”

I think we all hope that is what happens.