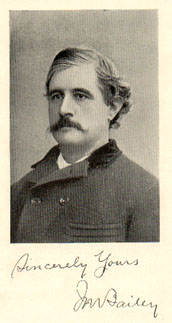

AKA “Manton”

J. Montgomery Bailey was the “correspondent” for the Danbury Times, contributing a vast amount of written material under such pseudonyms as “High Private Manton”, “Splifkins”, and others. His “Life in the Seventeenth” series ran throughout his three year enlistment. In the fall of 1863, following his capture at Gettysburg, he wrote a series entitled “Under Guard, OR, Sunny South in Slices”. This series covered his capture and subsequent imprisonment. Here are the first three installments, which cover his involvement in the Battle of Gettysburg, preceded by a very brief letter printed on July 9th – for many the first news they may have had about loved ones in Company C.

Gettysburg Capture

A brief letter from James Montgomery Bailey

The following note from James M. Bailey, Esq., from within the rebel lines, reaches us through Mr. Frank Butler:

Gettysburgh, Pa., July 2.

There was a fight here yesterday, in which our Reg’t. met somewhat of a loss. Geo. Sears, Lewis Bradley, Sergeant Wm. Daniels, Theodore Morris, Orin Bronson, Wm. F. Otis, Chas. Brotherton, Wm. Warren, James Hannon and myself, are prisoners, and in good health…(?)… friends of our position.

(signed) James M. Bailey

July 3rd. —They are paroling prisoners today but there is a division among the men regarding it. Some assert that our Government will not accept paroles within our lines. We are among that party, and have therefore taken our chance for Richmond, wanting a legal parole or none.

P.S.—John Jarvis, of Ridgefield, is here and safe.

Capt. Moore, Sergeants Dauchy, Bronson, and Barnum were seen to fall in the fight, but nothing definitely is known beyond that by us. I would also add that Corporal Horace Judd of Bethel is here safe, also, Richmond bound. God will be with us, and has, I believe, directed us in the right way.

Slice First

I well remember the night of the 30th of June. The sky was clear of clouds and filled with bright glittering stars. The moon threw a calm, mellow light over our camp, and the surrounding hills. We were lying at Emmittsburg in Maryland, near the Pennsylvania border. We felt that our marching was about done for the present, and that we were on the eve of a heavy struggle. The solemnity which always foreruns a battle, pervaded our minds, intensifying our thoughts of home, and weaving shadows of anxiety across our future. The conflict was imminent. All through the day flying rumors came on all sides. Lee had destroyed Harrisburg, routed the militia, and was rapidly advancing on us by way of Gettysburg. I stood leaning against a camp stake, gazing dreamily across the hill, with mind reverting to Chancellorsville and filled with anticipations of a second edition so soon to be issued. In imagination I was amid the carnage, surrounded by gleaming bayonets and staggering wounded, while the air resounded with the unearthly hiss and whiz of shot and shell, and piercing cries of the mangled combatants. While thus wrapt in bloody glory, I felt a hand laid on my shoulder, and a familiar whisper greeted me with the question,

“What are you thinking of — home?”

I roused myself from the sad reverie and turning around, voluntarily grasped the inquirer’s hand.

“No, Dick, I am not thinking of home, exactly, but of what is coming.”

“Yes, we have got to fight, Mont,” was his quiet rejoinder, “and somebody has got to die. I hope it isn’t you nor me, though I don’t suppose we are any better than others.”

“It will be a hard battle,” I said. “The boys have made up their minds that if whipped here, there will be but little peace for our army the remainder of the summer.”

“We ought to fight now if ever,” he energetically exclaimed. “This Corps will run, I know — but Mont, the 17th must stand up to it and do something for Chancellorsville. I ain’t much, myself, and may run equal to the best Dutchman in the crowd, but I hope to God I will do my duty even if I do get shot.”

I looked at him in admiration; the moon seemed to shine brighter than before, lighting up his flushed face, and sparkling eyes, testimony sufficient of the earnest fire burning within. I was proud of him then — proud of the Man who shone in danger as well as affliction. Oh! Dick, WELL.

For a while longer we watched Night’s Queen, and her myriad of glittering attendants, and then seeking our “shelter” fell asleep, to dream of home and the uncoffined grave. We expected to be on the move at daylight the next morning, but for some reason were not. The delay offered us time to get a good breakfast, with milk in our coffee, a meal never to be forgotten by me, as after circumstances fully justified. At eight o’clock our corps was in line, taking the Gettysburg trail, left in front. My journal does not state the heat of the atmosphere, nor whether the sun shone, and it’s so long since that I have forgotten, but I well remember the march was very fatiguing. We marched moderately enough for the first hour, then I noticed a perceptible quickening in the pace — limbs began to waver, and the second hour developed some pretty evident weariness, something hitherto unknown among us. At one period while filing through a piece of forest, the low rumbling report of a heavy gun sounded afar off on our front. It had an ominous import and gave rise to many an anxious glance.

“The signal gun Mont,” was the whisper by my side; “We must be up and doing.”

Here was our last halt. When we moved again, it was at an increased rate. Steadily we marched on, the brave boys exerting every effort to retain their files for the opening of the ball was sounding sullenly ahead. It would not look well to break down now, so thought all, but all could not support the principle. Lolling tongues, trembling limbs and short, heavy breathing denotes that the exertion was fast becoming superhuman. It was here that the Captain fell out. His absence was keenly felt by me. The heavy artillery roar ahead was drawing nearer and nearer, and I dreaded to enter the fray under any other leadership but his. Just before entering the town he rejoined us. Benson fell out about the same time. Poor fellow, he got back in time to be offered. Dick was at my side, just able to stagger along, yet firmly refusing to leave the ranks.

As we approached Gettysburg the clouds of smoke among the hills on the left of the village, showed the position and action of the First Corps. The 2nd and 3rd Divisions of our Corps were drawn up in line side of the road. We moved by them and took up our position on the advance.

As we passed through the principal street, the inhabitants thronged us with refreshments. The sight was a novel one, coming so unexpected, created quite an impression. I expected to find the place deserted, knowing that spherical case and “round solids” were not calculated to promote good fellowship, hence the surprise. One of the number, a young girl of no ordinary attraction, claimed my attention in particular. The reader will please recollect that it was no time for Cupidic emotions. She held a plate of cakes with one hand, the other being used in administering to the thirst of the wearied boys, from a pail that stood by her side. An Officer seeing her exposed condition, ordered her to retire.

“Why should I fear,” she proudly asked, “They are fighting for me and I will not leave them!”

I stepped to one side as we passed her and secured one of the cakes, at the same time giving her a glance that spoke volumes; the cakes I offered Dick.

“I can’t eat it,” he answered; “my God, I am full, heart and all.”

I felt that it was no time for one to indulge in sweet meats; something more substantial was being set out, and I repressed a sigh as I thought how indigestible it was.

A shell shrieking and screaming flew over our heads and buried itself in a neighboring yard. The salute was greeted with sundry remarks, such as “How are you?” “Rather sassy, ain’t you.” “Wait a bit and we’ll show you a trick worth two of that”, etc.

Passing nearly the length of the town, we turned to the left, and formed on its outer edge. Still the first Corps kept up the music, smartly assisted by one of our batteries, 4th U. S., at a long range. The men were very much excited, and the incessant roar and rattle on the left did not act as a cooler. Colonel Fowler was perfectly calm, and soon succeeded in quieting, although there were some that would snap their guns, and would require just so many lucid answers to their hundred and one nervous questions. Major Brady was ordered to take four companies out as skirmishers. Cos. A. B. F. and K. volunteered to go. I was heartily glad at their willingness, being so exhausted I could hardly move, and their going relieved us from what we should otherwise have had to do. But their relief availed us little. They had hardly passed from sight when we were ordered to advance, and the next moment the lead of the First Brigade crossed the road and double quicked through the wheat under a galling fire from a Secesh battery, posted beyond to the right. We passed through single file, cleared the next field, and formed on a slope near a point of woods, and about 250 rods from our former position. Dick dropped his knapsack, and flinging mine, I dogged a howler, and cast a hasty glance about me.

Slice Second

Had I owned the land in that neighborhood (Gettysburg) and wished to dispose of it, I would have described it as rolling in the advertisement. There were two ridges rising gradually as they approached to, and forming together at the point of woods referred to. The one on the left constituted a part of a flourishing wheat field, the opposite a meadow, being divided by a rail fence. On the left the 4th U. S. Battery took position, supported by the 25th and 107th Ohio of our Brigade, while the 1st Brigade moved up on the right to the woods. Our regiment and the 75th Ohio acted as a Reserve to the Battery and Brigade, resting on the right ridge, and forming a triangle with them. As soon as I became aware of the above, we were ordered to change our position, which we did by moving up to the woods, over two rail fences, and forming in line on the right of the first brigade.

I concluded if falling over fences was to be the principal occupation of the afternoon, I had better drop my trunk, which had a tendency to prevent an active move, and forced the impression, whenever I salaamed to a shell, that my back was just high enough to be in direct range. So I determined to dispense with the luxury, and dove my hand in it, to relieve it of a few necessary evils, when the order came to fall back. There was no time to sling it, so I clutched it in one hand, and hanging on to my Enfield with the other, went over those fences clack-a-ter-clack, to the tune of an Artillery jig, my bobbing knapsack, crazed and bewildered, catching my successor over the rails, exactly under his chin, to the imminent dislocation of his neck. Regaining the old ground, I rested the trunk and went headlong inside of it, searching for the necessaries. Then the order came to change front, and I was forced to reappear without accomplishing my object.

I was intending to express the deep state of my feeling about that period, but the thought that Pennsylvania was invaded, aided by two feet of musical R.R. iron, shut me up, and I moved and dogged with the rest. When we got quieted again I took a fresh chew, and completed another dive, just in time to hear the order to change back, and I came forth with a face unequalled by a boiled lobster, and with my back so far up that it came nigh scraping acquaintance of unpleasant closeness with a “spherical case” just going by on a through ticket. At the close of this last move Colonel Fowler bid us rest all we could, for we would need all our strength, adding with a laugh, “Beware of the big ones, boys, the little ones will take care of themselves,” referring to the shell flying over us, and the forthcoming bullets. The rebel battery on our right plied its calling industriously, but with little damage, throwing over.

During the execution of the last order, the 4th U.S. opened on a battery across the plain which was playing severely on the right of the 1st Corps. At the first discharge I like to have went through the top of my cap, it was so sudden and unexpected, and as for depth of tone, would nearly equal the 2nd Knapp at Chancellorsville. The boys unslung their knapsacks, and flung themselves full length on the ground, to await the opening of the play. I looked back of us, in search of the remainder of the Corps, but it was nowhere in sight; the fields between us and the town were free from troops. I thought it strange that just our Division– a 11th Corps Division at that– should be posted so far to the front. But if West Point does not qualify a man to do the military, what will? The last query silenced me, and dropping the subject, I primed my Dahlgren afresh, and looked up the hill. Meanwhile the ammunition of our battery gave out, as also hopes of a fresh supply. One of the guns came around to our right, and took up position covering the noisy sideshow that had troubled us so sorely. The last charge was rammed home, and in impatient expectation the men waited for the caissons.

It was at this juncture that the attack on our line began. The crack of rifles in the woods brought us to our feet. Another rattle followed, and then a continual roar. The 75th led up, as we in close column wheeled to the right. It was then that the first Brigade gave way, and simultaneous with the order to deploy and charge, the Germans struck us. All was confusion immediately. Such another Babel I never witnessed. The Dutch fumed, crowded, and swore, and our boys, determined to follow the brave Fowler, yelled defiantly, and forced their way through the timid sheep, up, up to the woods. As I gained the colors, there was a cry for us to cease firing, as we were shooting our men. One glance from the advancing line coming up through the trees was sufficient to allay my fears. That butternut colored suit never covered a Union frame and so I gave my Erricsson free rein. The fire had now grown terrific on both sides, but the decidedly superior advantage of the enemy, both in numbers and position, told heavy on us. Although a man is not apt to notice what occurs about him in the midst of leaden hail, yet I could not help but be aware that a fearful avalanche of death was sweeping through my Regiment. It was one continual hiss about my ears, and the boys dropped in rapid succession on both sides of me. The only one of our Company that I saw after we opened was Corporal Scott, whose rifle spoke well among the rest. The enemy continued to move slowly up, firing rapidly. The din had reached the standard of a hell, and then the order to retreat was given. Colonel Fowler shouted the command to us, and the next instant he reeled from the saddle, his brains striking the Adjutant, who was by his side. The 17th fell slowly back from that fatal ridge, with the victorious but desperately contested enemy within but a few feet of us.

While the battle was raging so hotly at the woods the officers of the 1st Brigade were endeavoring to rally and form their panic stricken crowd in our rear. By dint of the sword, revolver and a moderate dose of Teutonic brimstone, they succeeded in keeping them all together till we got to them. But a sight of the gray Sardines as they emerged from the woods, in addition to a heavy volley, operated similar to an emetic, and they threw themselves away in a decidedly loose manner. Affairs took a Chancellorsville hue at this period, every man for himself. Yet there was not the same amount of rallying, being confined exclusively to the 1st brigade officers, who flung up their swords in an agony of despair, and shouted “rally” till their voices reached their boots. The enemy were cautious about venturing out of the shelter of the woods, fearing an ambuscade in the wheat. Had they pressed on us closely, we could have filled more graves. The boys fell back in a more extravagant way then they did on the Rappahannock, taking advantage of every opportunity for an effective shot. I saw Rufus Warren as the rout became general. He lay on his side crying for help, but none could be given him then. He was the only one of our wounded that I saw. When I got about half way across the large wheat field, a general guide in the 1st brigade ran past me with his staff in his hand crying “Oh Gott, Oh Gott, how vill I get out of dis,” and the next instant he bounded in the air, throwing the staff from him, and striking full length in front of me, stiff in death. In his haste to get away from the bullets he got directly in range of one and it finished him.

Crossing the field I came to a lane, leading into the main street. Here I found a portion of the 75th under charge of a Lieutenant. They lay in the lane waiting for the rebs to come up. I got down with them, and by twisting about several times managed to stay nearly a minute, but my natural excitable temperament, coupled with an anxiety to find the Company, would not admit of my laying there, so I got up, and perched myself on the opposite fence for observation. I soon found enough to pay for the venture. In front of me were the Chivalrous bummers from the South, feeling their way along slowly up, maintaining a continuous fire. On the left the 1st Corps were still at it, although fast losing ground. Along the lane on the right where it struck the street was a large barn containing a number of our wounded and those that were not. One individual of the latter class attracted my attention at once, and held me riveted, to use a new expression. Loading his gun with a calmness and precision that enchained me, he stepped from the door, and resting his weapon against the corner, deliberately fired, keeping back himself, his tender heart refusing to see a man die. I hope folks in Harrisburg kept within doors, for there was danger in their streets about then. I watched the heaven born hero go through the motions several times, and fixing my rose bud of a mouth for a expansion, when a bullet struck the rail on which I was sitting, and without looking around to see who fired it, I went right over backwards into the field. Regaining my feet, I started for the town, following along back of the gardens till I came to a cross street.

In the main street I found the 4th U.S. drawn up to sweep through all obstacles with canister and grape. Men and officers of a dozen different commands were flocking up the street, shrieking out names of their regiments, commanding and countermanding. Frightened horses, swearing drivers, ambitious patriots, crazy citizens and the deuce only knows what, a conglomeration of all that was devilish, Babelish, and skittish. I sat down on a stone wondering where the 17th could have possibly got to. After a moments rest I moved up the street, as far as the Railroad crossing, and there I found five of our Company, with the colors, and a number of the regiment in charge of Captain Burr. George Brady caught sight of me, and yelled out my name in a tone slightly terrific. We had a shake hands, and then followed inquiries about absent ones. Wm. Otis informed me that Captain was killed, also the Orderly. Oh, God! I shall never forget the sensation that passed over me on the receipt of the news. Exciting as the scene was about me, I could realize the terrible loss that had come upon us. A Captain that was a Father; an Orderly that was a Brother. Noble, just and brave. They are gone forever from among us, but their memories will live in our hearts till time shall be no more.

The coming in of the skirmishers cut short all sad reflections. Major Brady now assumed command. Gen. Ames rode up, and getting the brigade in shape, marched us to the right of the town to check an advance of the enemy in that quarter. A few moments previous to this, the 2nd Division came up, and formed beyond us on the right, but one or two sound volleys weakened their knees, and sent them back into town as if chased by the itch. Encouraged by their success the enemy pushed up more rapidly. It was then that we were formed. We had a fine position in the rear of some lumber piles, where, unlike small children, we could be heard and not seen. The sight was a fine one. Beyond us were the enemy coming across the fields in straggling order, with that four square, dirty rag, trying to get up a flutter among them. On they come, while the music of our rifles sounded out a welcome to them. We were just getting warmed up, and I had secured a position out of reach of a hero behind me, who seemed determined to kill a Reb through my cranium, when we were ordered to retreat, and accordingly fell back to the old place at the rail road. Again the women of Gettysburg showed their bravery and devotion, supplying us with water and food as we fell back, perfectly regardless of sundry bullets that whistled, snug and hissed in their usual way.

We got back to the rail road street in time to meet the flying columns of the 1st Corps as they were driven in on our left. Then occurred Babel the third. The two Corps mixed and pushed up the main street, driving several hundred prisoners with them. Several ambulances got among them, increasing their facility for moving. The battery, having been through it all, determined to see it out, even through we had taken in another Corps and then brought up the rear. For my part the crowd was too thick, so I proposed to Otis to keep behind, taking advantage of the different shelter for using our guns. Otis agreed, and we entered upon a systematic course of street firing, which looks very pretty in print, but is not so nice in experience. But it is time to close for this week.

Slice Third

What little I saw of independent fighting behind the lumber piles, convinced me that it was none of the safest, but I judged it preferable to being in the masses surging above. I had a horror of bidding farewell to the world and Gettysburg in such a crowd, in fact, if I were going to get shot, I wanted it done in a legal way, that I might go off respectively, and not to be caught in eternity with my hands in my pocket not knowing how I came there. We stood on one of the four corners when making the decision. To the right and left on the outskirts of the town we could see squads of the enemy moving up, intending to flank us, with flattering prospects of success. Up the main street in full view were advancing Rebs, whose guns kept up a continual cracking; towards these Otis and I, with a few others, directed our attention. Getting in the cover of the buildings we would load rapidly, select our man, and let drive. It was very amusing to be sure, but doubly dangerous on account of a few excited unflinching Unionists, who talked fast, said tam instead of damn, kept in our rear, and shut their eyes when they fired. I kept about two thirds of my mind centered on these individuals. After hearing several distinct hisses in close neighborhood to my ears, and confronting two dark tubes, on a dead level with my phiz, which I just managed to dodge by instantly embracing the pavement, I concluded to keep an active watch on their heroism. A few moments after — or seconds, rather, as we were retreating back, I was startled by the outcries of a woman in deep distress. Looking around I saw a sight that turned my heart to ice, and held me rooted to the spot. Unheeding the whistling messengers of death and ruin; unshocked by the terrible scenes surrounding her, was a woman coming rapidly toward us, her eyes streaming with tears, hair disheveled, and hands clasped in mental agony. Never while

I live shall I forget that despairing face — those terrible cries. It needed no words from those ashen lips to explain the cause of such grief. The sights about us were freighted with painful suggestions. The son, the only one, perhaps, in the bloom of health, marched into his native town once more. The fond mother awaits him at the gate. He comes — a smile, a hasty kiss, and the columns move on. The roar of the battle awakes the echoes of his own native hills. Hours pass on — the waiting mother is again at her post, her eyes strained toward the “din and smoke”. Nearer, nearer it comes — they are on the retreat. Column after column passes — she recognizes a neighbor’s son in the mass, and she cries her darling’s name. The answer congeals her blood, crushes her heart, and blights her brain. Dead! dead! dead! All the horrors of her situation flash before me — my eyes become moist, and seeking to assuage her grief, I moved up to her side.

“My dear woman,” I exclaimed, “what evil has befallen you?”

She turned tearful eyes toward mine, and in tones of heart rending anguish moaned —

“My poor, poor horse, the dirty Rebs have stolen him!”

Recollecting that I was needlessly exposing myself, I rushed behind a corner, and continued the work of death. Simultaneous with the move, a gun of the battery, unnoticed by me, charged with grape, belched forth it’s contents, sweeping the street. I leaped nearly nine feet in the air, out of pure fright, but when I saw that I was not in two parts, got cooled down again. The gun could not of been more than two yards from, and nearly directly in front of us. The lead binding on the cartridge struck in under Otis’ feet. I first thought it was a premature discharge, and prayed that my relatives might find my legs. We continued to fall back through the town, the distance between us and the main column gradually increasing, although unnoticed at the time. An incident occurred here, which is seldom known in any other position of the Army but our Corps, where it is of frequent occurrence, and which I must not omit to mention. While engaged in loading, I noticed a member of the 1st Brigade step out on the walk and take a deliberate aim down the street.

Seized by a desire to see how good he was on a bead I got behind him, and glanced along his rifle. The sight that met my eye, gave me a start equal to that by the woman. Instead of a festive seceder, armed to the teeth and beyond, I saw a member of the first Corps advancing slowly toward us, his face streaming with blood from a bad wound on his head, and his left arm literally a mass of mangled flesh. It was all comprehended in an instant, and horror struck I cried out —

“Good heavens, man, put down your gun; you are trying to kill our own men!”

He dropped his gun, muttering something that I did not understand. I felt to pity him for his ignorance and by way of consolation told him he was a poor cuss. The whole affair took up but a moment’s time, but when I looked back again, I found that the enemy’s mounted infantry had got between us and our friends, and we were bagged. To the right and left were heavy bodies of the gray wretches, while in our front were massed the greater part of their forces, although the street to the edge of the town was comparatively free of them. I looked about me for some place of concealment, possessed with the idea that if we could only hide ourselves till the next day, we would be released by our folks, who would undoubtedly get possession of the town through the night. But I looked in the vain, not the slightest opening appeared, and waited for the unfolding of our destiny. Otis concluded that it was time to give up, but he had his doubts about the safety of waiting in the street for the fatal circle close upon us, as some of the men were rather careless in their manner of taking prisoners, often getting the fire before the halt. An instant sufficed to arrive at these conclusions, and during the next we dashed across the street, over an iron fence, up the steps and into a church transformed into a hospital. We had barely executed this remarkable feat of legship, when the pavement resounded to the clatter of hoofs, while the air was filled with shouts and musketry. I looked out upon the streets and shall not soon forget the impressions I received from what I saw. There was about a dozen Confederates standing together; others were forcing open doors, with an eye to the buttery, and some were engaged in bringing in prisoners or bringing them down, while up and down, around and about, dashed the mounted infantry, their uncouth rigs, slouched hats with trailing feather forcibly reminding me of pictures of brigand scenes in olden Spain. How long I would have leaned there on my gun and gazed on the quaint tableaux before me, I know not, probably till now, possibly not; but the entrance of a Confederate officer turned my attention, and I began to look around me. I was standing in the porch at the time. There were two tables at which two surgeons were operating. A little old woman with a motherly expression of face was busily engaged in fulfilling the sex’s holiest mission, human alleviation, rather a pretty idea that. I now entered the main body of the building. The pews had been turned into beds, and were nearly filled with wounded from both sides. Reader, did you ever stand within a Church hospital? If not, the first time you enter your sanctuary imagine the pews transformed into bunks, on which lie stretched scores of mangled men, writhing, moaning and sobbing with pain, the aisles filled with little pools of blood, and the pulpit, from which you have heard sound the gentle language of the Prince of Peace covered with diversity of bloody, powder begrimed weapons, and you will get an idea of my impressions as I looked into the room. My heart was touched with their cries, and seeing that it was impossible for the old lady to attend to all their wants, the doctors being busy at the tables, Otis and I hid all that pertained to us in the field, and began the part of the Samaritan, as far as possible. I will not deny that I was prompted by another idea than that of sympathy. I thought that if we could but disguise our calling under that of hospital attaché, known to the vulgar as doctor’s pimps, we might possibly evade suspicion and manage to get off after all. Like a number of others of my brilliant projects, it proved — but I will not anticipate. During our ministration several villains looked in upon us, but did not disturb us. At such periods I redoubled my energies, and doubtless appeared as a first class combination of physic and patience, in their estimation. I thought once of passing myself off as a Hospital Steward, but recollecting that the rear ranks of my unmentionables was in a state that would preclude such an idea, I gave it up. The water giving out, I took the pail and sallied out, taking particular pains to make my errand known to the Rebs about me. In the center of one group, I saw the lady that had probably lost a son. I heard the word horse and moved off one side. Encountering an officer next, I asked if he knew where I could get any water, “as it was greatly needed at the hospital for the wounded,” laying a stress on the hospital.

“No, I could not, my boy,” he replied, “and sorry am I too, for the poor boys want it. In some of the yards you will find a pump I reckon.”

Following his “reckoning” I entered an alleyway, and followed it into a back yard, where I found a goodly well, as also a large outhouse in which four traitors were devouring cold ham, bread and butter, etc. While I was drawing the water, one of them accosted me with —

“Ho, Yankee, ar’ yer gettin’ that for the hospital?”

“Yes.”

“Hard day this, eh Yank?”

I modestly agreed with him.

“Damned hot, poor fellows,” and with this remark he picked up his gun and left the yard. I followed after, inwardly chuckling at the success of my ruse, and indulging in flattering prospects of the future.

“Ah Dick I’ll have a long story to tell you when I get back,” I mentally observed.

At the street entrance I found quite a crowd, who looking upon me as a public benefactor furnished expressly for the occasion, pitched into the pail, and despite my expostulations, seasoned by a score of damns from the unselfish they drank it all.

“Get another pail full, Yankee, and the first man that wants a drink, give him the whole of it, smack in the snoot; I would,” observed one of the crowd, a six footed Texan.

I returned to fill my pail, inwardly estimating how big a piece of Manton would be left in case I should accidentally became absent minded and profit by the disinterested advice. Just as I reached the well for the second time, I felt a hand on my shoulder and turning about, I confronted a Corporal in that bewitching way, who with a lovely, condescending, smile, for the reader must not forget his rank, opened conversation.

“Aint you the one that got the water here just now?”

“I am” I replied, wondering what the deuce that was to him.

“Yes, just the man I want then; YER MY PRISONER.”

I can never forget the smile that played on his face as he delivered the announcement, a mingling of triumph and regret, and very strange in comparison with the surrounding circumstance. For the moment I was nearly prostrated, the intelligence was so unexpected. I had crept up very high in the last half hour and it was grievous to fall so far. I closed my eyes to all about me, while my mind traveled into futurity. Richmond and all it’s horrors rose before me. A long, dreary imprisonment, slow starvation, cruel torture, painful disease and agonizing suspense. A half-repressed shudder passed over my frame, and then I put away the picture, and came back to the little yard, my captor and my errand.

It seemed as if he had followed my thoughts, for he said,

“It’s hard Yankee, but its duty; I know how you feel,” then as if to assure me, he quickly added, “You’ll be treated well, no fear of that. We use you better than yer boys use us sometimes, but then it ain’t for me to judge that; God knows I don’t want to retaliate on you. Cheer up, my boy; it’s yer misfortune now, it may be mine next time. I wish there was peace again, and this murdering over.”

“Amen,” I heartily responded.

I took up the pail, while he slung his gun over his shoulder, and we started for the hospital. Ah, Dick!